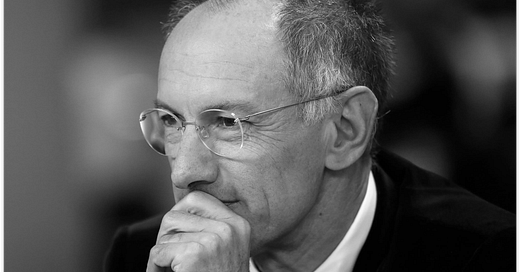

Sequoia Capital’s Michael Moritz on the way up 30 years ago today

Mr. joined Sequoia in 1986 after a career in journalism. In 1993, he was still hitting his VC stride, and before he went on to seed-fund Yahoo!, Paypal, Google, YouTube Zappos, and dozens of hits.

By Anthony Perkins

From May 1993 issue of Red Herring

Perkins: You made a pretty big jump from journalism to venture capital. Other than the fact that you had been an observer of the business, why do you think you were offered the opportunity to join Sequoia?

Moritz: I think there are two sorts of venture capital firms. One firm likes to recruit partners who are identical to the people sitting around the table -- folks who have been to the same schools, people who got married at roughly the same period in life and have the same number of children, and people who have spent the obligatory amount of time at either H-P or Intel. Other firms try to bring together an eclectic group of partners because they believe in gaining the perspectives of people from different backgrounds. This has always been the approach used at Sequoia. That's why I think the people here were willing to take a flyer on me.

Perkins: What makes a good venture capitalist?

Moritz: Don Valentine [Sequoia founding partner] will tell you that, to this day, he has no idea what makes a successful venture capitalist. He always uses Arthur Rock as an example. Arthur's life prior to becoming a venture capitalist did not for one moment suggest that he was going to be the incredible, spectacular, out-of-the-park home-run hitter that he became. Bill Hambrecht is another example. The best I can recall was that he was a history major prior to becoming an early force in venture capital and the pioneer of technology investment banking. Then there have been people who have come into the business with blue-chip, gold-plated, platinum-tipped resumes who have flamed out.

Perkins: Do you have a role model in the venture business?

Moritz: The closest role models for me are right here at Sequoia because these are the guys I have worked with for a long time, and they are all very successful people. There are attributes that each of the partners possesses that are fabulous. Don [Valentine] is a cool and very rational thinker when it comes to analyzing companies and different situations, Pierre [LaMond] has a tremendous competitive drive, and Gordon [Russell] radiates a friendly courtliness. Contemplating those attributes is very helpful as I think about how to conduct myself in the venture business. But I don't believe in modeling myself after one particular bronze bust.

Perkins: When you look across the venture capital landscape, what are Sequoia Capital's competitive advantages?

Moritz: We have a very tight focus on making sure there is a sizable market opportunity in front of us before we make an investment. We are much more focused on the market growth potential and the ability of a company to reach a market successfully and profitably. We have also demonstrated, as a firm and individually, the ability to get companies off the ground with a small amount of fuel. We like to start wicked infernos with a single match rather than two million gallons of kerosene. This is clearly a differentiated way of getting a company put together. This approach has terrific benefits for the people who start the companies and for all of our limited partners. You might say that we have a morbid fascination with our ROI, as opposed to the amount of dollars we put to work. And this is a very, very, very different message than you get from a lot of other venture firms.

We have a very tight focus on making sure there is a sizable market opportunity in front of us before we make an investment. We like to start wicked infernos with a single match rather than two million gallons of kerosene.

Perkins: Our observation is that there is a relationship between the amount of equity capital a technology company requires to get off the ground and the prospects for the company's success. Basically, the more money a company needs, the less likely it will be successful. Would you agree?

Moritz: Yes, I think that's true. There are few exceptions where we have felt or were convinced by others that there was a real need to spend money because everyone was afraid that if the company's product didn't quickly make it to market, its window of opportunity would evaporate. That would be about the only way we could get coaxed into investing more rather than less money into a company. We are big believers in the notion that lesser is better. This approach forces companies to be more disciplined -- they are hungrier, and they worry about how they spend pennies. Frugality is a real virtue. And that attitude starts around here. We save paper clips.

Perkins: Did you pass on the 3DO deal because you thought it would take too much capital to be successful?

Moritz: Electronic Arts started in Sequoia's office a long time ago. So Trip Hawkins occupies a permanent place in the Sequoia Capital Hall of Fame. The issue we had with 3DO was the question of how many people would be prepared to shell out $700 for a box that sat on top of their television. If the proposition had been $199 for that box, with Trip running the company, we would have become believers.

Perkins: In the case of 3DO and Nationwide Network, Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield & Byers appears to have pursued a strategy in which they were the sole venture investor in each deal, and they leveraged their investment by raising money, presumably at higher valuations, from corporate partners. Is this a strategy you would consider?

Moritz: It's a strategy we have employed. Our portfolio company C-Cube, for example, has Texas Instruments as a corporate partner. Corporate partnering is a fact of life in the biotechnology and medical industry. It's an interesting and often necessary way to proceed, but it's not the only way to be successful.

Perkins: Hasn't C-Cube raised and spent a ton of money? Didn't they violate The Eleventh Commandment?

Moritz: We financed effectively the restart of C-Cube. Don and Pierre are working very closely on the deal -- so we are using maximum firepower! (laughs) Don is the chairman, and Pierre runs the engineering department while a search is underway. The president of C-Cube, Bill O'Meara, is one of the founders of LSI Logic and a partner of ours. So we have surrounded the company.

Perkins: How often does a Sequoia partner actually go in and help operate a company?

Perkins: Pierre is the great unsung hero of Cisco Systems. He spent a tremendous amount of time at the company, working behind the scenes and helping to make sure the engineering department was designing and getting new products to market. People don't realize the significant contribution Pierre made to Cisco because Don's name is on the hubcaps as the chairman of the company. The ability we have to help operate companies is a very useful tool in our arsenal.

Perkins: Sequoia's image on the streets of Silicon Valley is that you are the Los Angeles Raiders of venture capital -- the tough guys who are quicker than the other firms to boot the CEO or pull the financial plug.

Moritz: We are congenitally incapable of pouring good money after bad. Some people, for their own purposes, will thrust us into a position to be harbingers of bad news to management, which is all right. But we do not want to continue propping up a company if we think its chances for success have evaporated. We would be wasting our money as individuals and wasting the money of our limited partners. There have been very few instances when we decided to stop funding a company and regretted it.

Perkins: What's the hardest part of your job?

Moritz: We usually don't make mistakes when assessing the market opportunity. And we are reasonably accurate in predicting how long it will take to bring a product to market. The great imponderable is to judge accurately and predict how well a president is going to be able to run the business. It is easy to mistake the façade for reality.

Perkins: What characteristics does Sequoia look for in a company president?

Moritz: Frugality, competitiveness, confidence, and paranoia.

Perkins: Where is Sequoia investing its money these days?

Moritz: We continue to mine the territories in which we have traditionally been successful. There's tremendous opportunity in digital video. C-Cube is positioned right at the center of that universe. I suspect that our investment there will lead to lots of other opportunities in ancillary companies that depend on some of the technology C-Cube is deploying. The internetworking business also has stacks of opportunities. This is a segment that has done well for us and, we expect, will continue to do well for us. Since Cisco, we've invested in Magellan, a GPS company; Positive Communications, a paging company; and SpectraLink, a wireless in-building telephone company. One other area is the software business. In the late 1990s, object-oriented technology will enable the disassembly of large, monolithic applications and will provide people with the building blocks to tailor and fashion the tools they will need every day.

Perkins: Tom Perkins preaches to his troops that you invest in technology products that are ten times better than existing products because by the time you get to market, they are only going to be two times better. Would you agree with that?

Moritz: It's always nice to invest in a company with a massive technology advantage. But we have been able to help build companies that perhaps don't have a 10x technology advantage but are able to get to market early and build a formidable sales and distribution machine that becomes a very difficult barrier for others to hurdle. Cisco Systems is a classic example. So it's really the marriage of good technology and great channels that make competitive companies.

Perkins: Once a company is up and running, what do you watch out for?

Moritz: We are perpetually vigilant and concerned that companies have a 12-cylinder product development engine that isn't going to sputter. What will ultimately kill almost every technology company is a product development engine that begins to sputter and backfire. The Valley is littered with companies whose development engine has failed. It's very tempting for companies to coast on the success of their first product. They forget that the only reason that they're in business is that they took advantage of a fellow at a big company who fell asleep at the product development wheel.

Perkins: Kevin Compton at KPCB told us that of the 150 deals they have funded, none came over the transom. Is it ditto for Sequoia?

Moritz: We're always asking that question around here, and we struggle to find the answer. Ultimately, a deal has to stand on its own, no matter how it is referred into the partnership. So our message to entrepreneurs is that our doors are wide open. If you can leap tall buildings in a single stride, we would like to hear your story.